I completed my PhD at the University of Sydney in early 2020. My research was in human-wildlife conflict, focusing on understanding and enabling coexistence between predators and livestock, and using the Australian dingo as a case study.

Here’s a quick summary of my findings:

- Tools to protect livestock: There hasn’t been consistent and appropriate monitoring of the effectiveness of tools intended to protect livestock from predators, meaning we invest a lot of time and money into management with limited understanding of what actually works. This is the case not just in Australia, but all over the world. The evidence we do have suggests that nonlethal tools can be effective. I wrote two review papers on this topic (here and here).

- History of dingo-livestock conflict: By analysing responses to a previously unpublished survey of graziers’ interactions with and perceptions of dingoes from the 1950s, I was able to explore how historical context might have shaped contemporary management. Perceptions of dingoes as a pest have been tied strongly to sheep production, especially important at the time of the survey when Australia was ‘riding on the back of the sheep’ due to booming wool value. This meant scaling up control efforts, and around this time, aerial baiting began to be rolled out at a broader scale, despite perceptions from graziers that it wasn’t protecting their livestock. The main tools used today have not changed greatly since the 1950s, continuing to comprise poison baiting, shooting, trapping, and fencing.

- Then and now: I repeated some of the questions from the previous study in a new survey to identify how attitudes and behaviours had changed. This included surveying 23 of the same properties that had been surveyed in the 1950s. Again, I found that attitudes and the tools used hadn’t changed greatly, with views that dingoes are a pest remaining dominant. However, a small number (3) of respondents specifically stated that they do not use lethal dingo control, including for reasons that they don’t consider dingoes to be a pest and that they view dingoes as part of the natural environment.

- What shapes behaviour? In the new survey, I also explored socio-psychological factors that might predict whether livestock producers use lethal dingo control tools. I found that values (e.g., whether you perceive wildlife to have intrinsic value), beliefs about dingoes (e.g, whether you consider them to play a positive ecological role), perception of the risk dingoes pose to your livestock, and your social identity (e.g., whether you see yourself as an environmentalist, pest controller, etc.) to be significantly linked to dingo management behaviours. All of these factors were also linked to one another, but social identity was the most useful predictor of behaviour. This shows that understanding social norms can be more important than mitigating risk in influencing behaviour.

- What does the public know and think about dingoes and their management? Through an online survey of the public, I found that less than a third of Australians are aware that dingoes are legally controlled and that attitudes towards commonly used lethal dingo control tools are generally negative. Attitudes towards dingo control were linked with social identity and also whether respondents viewed dingoes as native vs non-native and the extent to which they considered dingoes to be a pest. This is important because the dingo’s identity in Australia is ambiguous with disagreement about whether it should be considered native, having likely been brought to Australia by humans at least 3500 years ago.

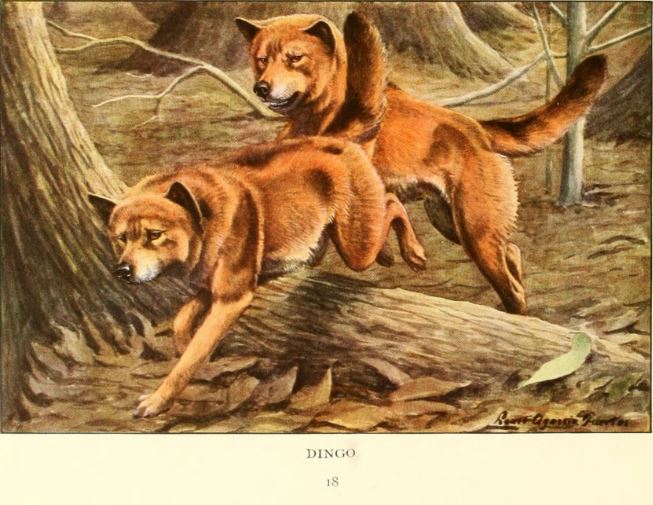

- What is a dingo? Another factor contributing to the dingo’s ambiguous identity is the fact that they are closely related to domestic dogs and have interbred with domestic dogs across large areas of their range. This leads to disagreement about how to classify a free-living dog in Australia and what (if any) level of hybridisation between dingoes and domestic dogs is acceptable. Is a dingo still a dingo if it has some degree of domestic dog ancestry? Who should decide this? In making decisions about management priorities, decision-makers need to consider ethical questions about the value of dingoes in ecosystems and human society (e.g., Traditional Owners and broader public) and whether hybridisation might affect this value.

- “Dingoes” or “wild dogs”? Because of this hybridisation with domestic dogs, management of wild canids is typically described as “wild dog” management, encompassing dingoes, feral dogs, and their hybrids. Through my public survey, I also found that the use of terminology like “wild dogs” is likely to affect awareness and perceptions. People viewed “wild dogs” negatively and “dingoes” positively, and yet less than a fifth of respondents were aware that dingoes are included in “wild dogs” when describing management. This illustrates that how an issue is framed and the terminology we use can have important consequences for public understanding of an environmental management issue like dingo control. This paper is in press and the link will be added in due course.

I’ve provided links to my publications that document these findings. If there are any that you aren’t able to access but would like to read, please don’t hesitate to contact me and I will gladly provide you a copy.

Leave a comment